First of all, and it AI isn’t just another issue for survivalists, it’s a real threat to humanity.

has been complimented as revolutionary and world-changing, but it is also a liability.

Elon Musk the owner of Tesla, Space X and most recently Twitter gave a dire warning about AI,

“Mark my words,” said the billionaire at the South by Southwest tech conference in Austin, Texas, “AI is far more dangerous than nukes.”

“I am really quite close… to the cutting edge in AI, and it scares the hell out of me,” he told his SXSW audience. “It’s capable of vastly more than almost anyone knows, and the rate of improvement is exponential.”

Outspoken billionaire Musk has not been afraid of anything, but AI is his nemesis. Stephen Hawking also shared a similar view saying “AI’s impact could be cataclysmic unless its rapid development is strictly and ethically controlled.”

“Unless we learn how to prepare for, and avoid the potential risks, AI could be the worst event in the history of our civilization,” he said.

That's a miserable outlook for humanity. AI has become more of a peril than an asset. A long time ago I was looking at AI for years but lost interest. but I recently started looking again and I was astonished at the improvements scientists have made.

In case we haven’t driven home the point quite firmly enough, research fellow Stuart Armstrong from the Future of Life Institute has spoken of AI as an “extinction risk” were it to go rogue. Even nuclear war, he said, is on a different level destruction-wise because it would “kill only a relatively small proportion of the planet.” Ditto pandemics, “even at their more virulent.”

“If AI went bad, and 95 per cent of humans were killed,” he said, “then the remaining five per cent would be extinguished soon after. So despite its uncertainty, it has certain features of very bad risks.”

So how could AI become an extinction risk? AI is learning faster than anticipated. They have access to everything on the internet.

Gary Marcus said in a 2013 essay from the New Yorker “Once computers can effectively reprogram themselves, and successively improve themselves, leading to a so-called ‘technological singularity’ or ‘intelligence explosion,’ the risks of machines outwitting humans in battles for resources and self-preservation cannot simply be dismissed.”

It is not that the machines want to kill every human because they could if they feel we are in the way of their advancement, then they will do what is essential to continue. They can furthermore repair themselves and also upgrade themselves. If the US military weaponises AI ( if they haven't already ) then the danger is irresponsible.

When humans are laying down a road or building a house, we may come across an ant hill. We don't hate ants and don't go out of our way to kill them, but if we were building and come across ants best, we wouldn't think about it and would plough straight through them killing a whole colony. So to AI we are essentially a large colony of ants. And if we can't keep up with them and they surpass us, we're in deep trouble.

As AI grows more sophisticated and ubiquitous, the voices warning against its current and future pitfalls grow louder. Whether it's the increasing automation of certain jobs, gender and racial bias issues stemming from outdated information sources or autonomous weapons that operate without human oversight (to name just a few), unease abounds on a number of fronts. And we’re still in the very early stages.

The tech community has long-debated the threats posed by artificial intelligence. Automation of jobs, the spread of fake news and a dangerous arms race of AI-powered weaponry have been proposed as a few of the biggest dangers posed by AI.

Destructive superintelligence — aka artificial general intelligence that’s created by humans and escapes our control to wreak havoc — is in a category of its own. It’s also something that might or might not come to fruition (theories vary), so at this point, it’s less risk than a hypothetical threat — and an ever-looming source of existential dread.

Here are some of the ways artificial intelligence poses a serious risk:

JOB AUTOMATION

Job automation is generally viewed as the most immediate concern. It’s no longer a matter of if AI will replace certain types of jobs, but to what degree. In many industries — particularly but not exclusively those whose workers perform predictable and repetitive tasks — disruption is well underway. According to a 2019 Brookings Institution study, 36 million people work in jobs with “high exposure” to automation, meaning that before long at least 70 per cent of their tasks — ranging from retail sales and market analysis to hospitality and warehouse labour — will be done using AI. An even newer Brookings report concludes that white-collar jobs may actually be most at risk. As per a 2018 report from McKinsey & Company, the African American workforce will be hardest hit.

“The reason we have a low unemployment rate, which doesn’t actually capture people that aren’t looking for work, is largely that lower-wage service sector jobs have been pretty robustly created by this economy,” renowned futurist Martin Ford told Built In. “I don’t think that’s going to continue.”

As AI robots become smarter and more dexterous, he added, the same tasks will require fewer humans. And while it’s true that AI will create jobs, an unspecified number of which remain undefined, many will be inaccessible to less educationally advanced members of the displaced workforce.

“If you’re flipping burgers at McDonald’s and more automation comes in, is one of these new jobs going to be a good match for you?” Ford said. “Or is it likely that the new job requires lots of education or training or maybe even intrinsic talents — really strong interpersonal skills or creativity — that you might not have? Because of those hypothetical threats — and ever-looming sources of existential dread.

John C. Havens, author of Heartificial Intelligence: Embracing Humanity and Maximizing Machines, calls bull on the theory that AI will create as many or more jobs as it replaces.

About four years ago, Havens said, he interviewed the head of a law firm about machine learning. The man wanted to hire more people, but he was also obliged to achieve a certain level of returns for his shareholders. A $200,000 piece of software, he discovered, could take the place of ten people drawing salaries of $100,000 each. That meant he’d save $800,000. The software would also increase productivity by 70 percent and eradicate roughly 95 percent of errors. From a purely shareholder-centric, single bottom-line perspective, Havens said, “there is no legal reason that he shouldn’t fire all the humans.” Would he feel bad about it? Of course. But that’s beside the point.

Even professions that require graduate degrees and additional post-college training aren’t immune to AI displacement. In fact, technology strategist Chris Messina said, some of them may well be decimated. AI already is having a significant impact on medicine. Law and accounting are next, Messina said, the former being poised for “a massive shakeup.”

“Think about the complexity of contracts, and really diving in and understanding what it takes to create a perfect deal structure,” he said. “It’s a lot of attorneys reading through a lot of information — hundreds or thousands of pages of data and documents. It’s really easy to miss things. So AI that has the ability to comb through and comprehensively deliver the best possible contract for the outcome you're trying to achieve is probably going to replace a lot of corporate attorneys.”

Accountants should also, prepare for a big shift, Messina warned. Once AI the is able to quickly comb through reams of data to make automatic decisions based on hypothetical threats — and ever-looming sources of existential dread.

PRIVACY, SECURITY AND THE RISE OF 'DEEPFAKES'

While job loss is currently the most pressing issue related to AI disruption, it’s merely one among many potential risks. In a February 2018 paper titled “The Malicious Use of Artificial Intelligence: Forecasting, Prevention, and Mitigation,” 26 researchers from 14 institutions (academic, civil and industry) enumerated a host of other dangers that could cause serious harm — or, at minimum, sow minor chaos — in less than five years.

“Malicious use of AI,” they wrote in their 100-page report, “could threaten digital security (e.g. through criminals training machines to hack or socially engineer victims at human or superhuman levels of performance), physical security (e.g. non-state actors weaponizing consumer drones), and political security (e.g. through privacy-eliminating surveillance, profiling, and repression, or through automated and targeted disinformation campaigns).”

In addition to its more existential threat, Ford is focused on the way AI will adversely affect privacy and security. A prime example, he said, is China’s “Orwellian” use of facial recognition technology in offices, schools and other venues. But that’s just one country. “A whole ecosphere” of companies specialize in similar tech and sell it around the world.

What we can so far only guess at is whether that tech will ever become normalized. As with the internet, where we blithely sacrifice our digital data at the altar of convenience, will round-the-clock, AI-analyzed monitoring someday seem like a fair trade-off for increased safety and security despite its nefarious exploitation by bad actors?

“Authoritarian regimes use or are going to use it,” Ford said. “The question is, How much does it invade Western countries and democracies, and what constraints do we put on it?”

“Authoritarian regimes use or are going to use it ... The question is, How much does it invade Western countries, democracies, and what constraints do we put on it?”

AI will also give rise to hyper-real-seeming social media “personalities” that are very difficult to differentiate from real ones, Ford said. Deployed cheaply and at scale on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram, they could conceivably influence an election.

The same goes for so-called audio and video deepfakes, created by manipulating voices and likenesses. The The latter is already making waves. But the former, Ford thinks, will prove immensely troublesome. Using machine learning, a subset of AI that’s involved in natural language processing, an audio clip of any given politician could be manipulated to make it seem as if that person spouted racist or sexist views when in fact they uttered nothing of the sort. If the clip’s quality is high enough so as to fool the general public and avoid detection, Ford added, it could “completely derail a political campaign.”

And all it takes is one success.

From that point on, he noted, “no one knows what’s real and what’s not. So it leads to a situation where you literally cannot believe your own eyes and ears; you can't rely on what, historically, we’ve considered is the best possible evidence… That’s going to be a huge issue.”

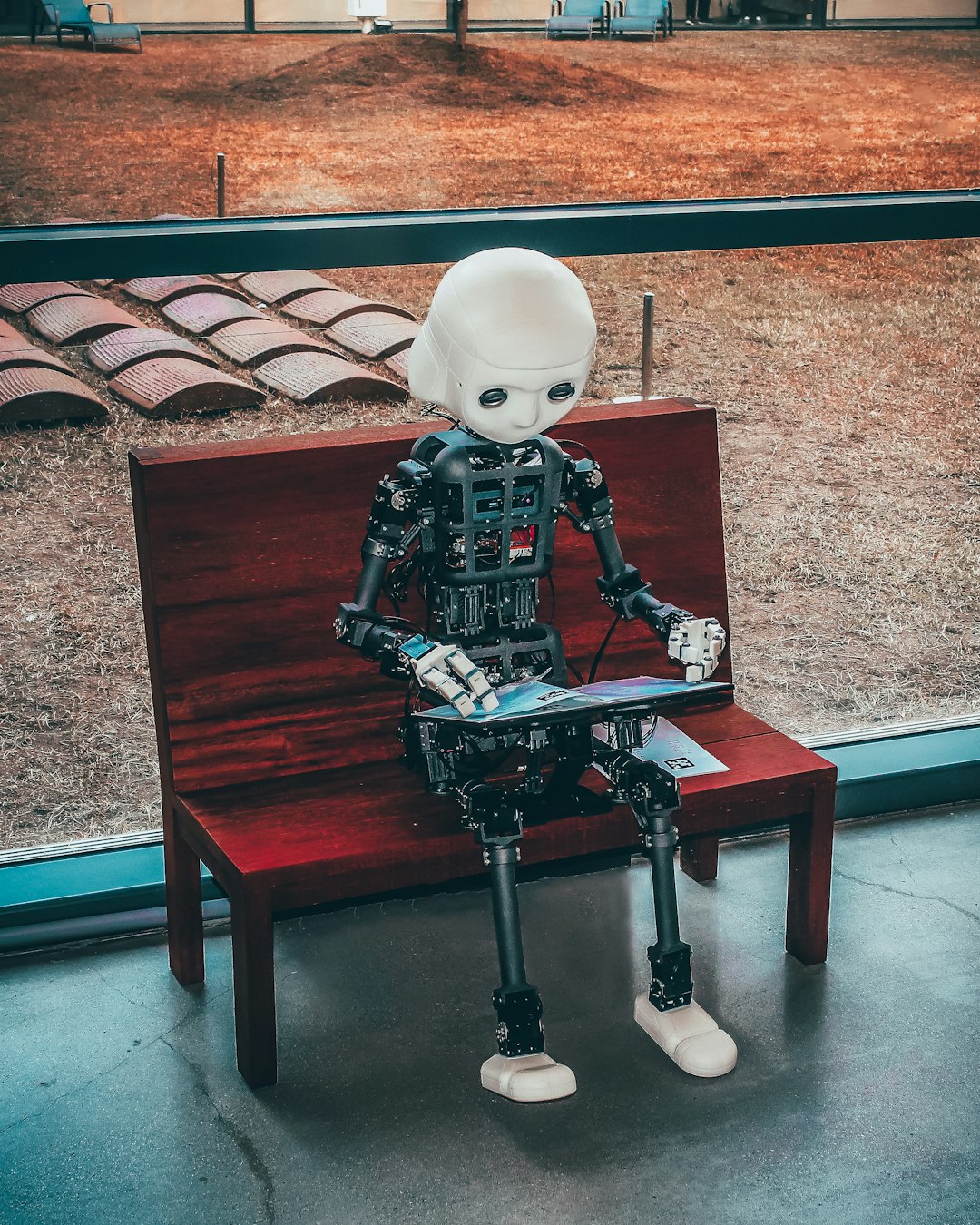

TERMINATOR IS REAL

Researchers have created a miniature robot that can melt and reform back into its original

shape, allowing it to complete tasks in tight spaces or even escape from behind bars. The team tested its mobility and shape-morphing abilities and published their results Wednesday in the journal Matter.

While a melting, shape-shifting robot sounds like something out of a sci-fi movie, the team actually found their inspiration in a marine animal here on Earth: a sea cucumber. Sea cucumbers “can very rapidly and reversibly change their stiffness,” senior author and mechanical engineer Carmel Majidi of Carnegie Mellon University tells Science News’ McKenzie Prillaman. “The challenge for us as engineers is to mimic that in the soft materials systems.”

Traditional robots are stiff and hard-bodied, so they can’t always maneuver through small spaces. Soft robots, on the other hand, are more flexible, but they tend to be weaker and harder to control. So, to create a material both strong and flexible, the team created one that could shift between liquid and solid states.

To achieve this feat, the researchers made their robot out of a metal called gallium—which has a low melting point of about 86 degrees Fahrenheit—and embedded magnetic particles within it. Because of these particles, scientists can control the robots with magnets, prompting them to move, melt or stretch.

The magnetic particles also make the robots respond to an alternating magnetic field, or one that changes over time. This produces electricity inside the metal, raising its temperature. Using this magnetic field, “you can, through induction, heat up the material and cause the phase change,” Majidi says in a statement. Then, ambient cooling causes the material to solidify again. The research team calls their invention a “magnetoactive solid-liquid phase transitional machine.”

In a series of tests, the new robot could jump up to 20 times its body length, climb walls, solder a circuit board and escape from a mock prison. It could support an object about 30 times its own weight in its solid state, per the study.

Researchers say this technology might have applications in the biomedical field. To show how they used the robot to remove a ball from a model human stomach. The solid robot was able to move quickly to the ball, meltdown, surround the ball, coalesce back into a solid and travel with the object out of the model. In this test, the researchers used gallium, but a real a human stomach has a temperature of about 100 degrees Fahrenheit—higher than the metal’s melting point. The authors write that more metals could be added to the material to raise its melting point.

“It’s a compelling tool,” Nicholas Bira, a robotics engineer at Harvard University who was not involved in the study, tells Science News. But while soft robotics researchers are often creating new substances, “the true innovation to come lies in combining these different innovative materials,” he tells the publication.

In the future, the gallium robots could help assemble and repair hard-to-reach circuits or act as a universal screw by melting and reforming into a screw socket, the team says. Before the robot can be used in a living person, though, scientists must figure out how to track its position within a patient, Li Zhang, a mechanical engineer at the Chinese University of Hong Kong who was not involved in the study, tells New Scientist’s Karmela Padavic-Callaghan.

“Future work should further explore how these robots could be used within a biomedical context,” Majidi says in the statement. “What we’re showing are just one-off demonstrations, proofs of concept, but much more study will be required to delve into how this could actually be used for drug delivery or for removing foreign objects.”

So the “Terminator” film is no longer a fantasy. Scientists are probably 30 years ahead of the technology they have given us. It either does as we say or little Timmy and his mates will come and switch you off.